The Right Left Turns

Description

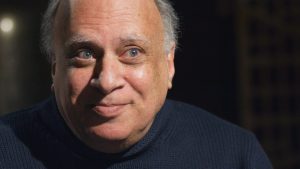

- For the past 40 years, Arthur Yorinks has been the power behind the throne for many of America’s most significant artists. But his work stands on its own.

- Karen Russell’s stories live in a space between the everyday and the surreal.

- Jason deCaires Taylor’s greatest assets are underwater. All of his sculptures are entrusted to the oceans.

Featured Artists

Arthur Yorinks is an esteemed and versatile writer. His work spans opera, theater, dance, film, radio, and children’s books. His 1986 collaboration Hey, Al with illustrator Richard Egielski won the Caldecott Medal, the highest honor for a picture book.

Yorinks was born in 1953 in Roslyn, NY, and attended Hofstra New College. He met Maurice Sendak as a teenager and collaborated with the famed illustrator on five children’s books. Together, they founded Night Kitchen Theater, which produces plays for kids. Yorinks is adapting Sendak’s most famous work, Where the Wild Things Are, for the stage for a 2023 premiere.

As well as writing over forty books for children, Yorinks has completed two opera librettos for renowned composer Philip Glass; helped create a full-length dance-theater piece with dance company Pilobolus; and wrote and directed numerous original audio plays performed live at the Kennedy Center and other venues and broadcast on SiriusXM Satellite Radio and New York Public Radio.

Jason deCaires Taylor is a pioneering sculptor. He created the world’s first underwater sculpture park, a work listed as one of National Geographic’s twenty-five wonders of the world.

Born in 1974 to an English father and Guyanese mother, Taylor grew up in Malaysia and England, and studied sculpture at the London Institute of Arts. He was living in Grenada as a diving instructor when he started constructing the Molinere Underwater Sculpture Park, which opened to the public in 2006. This led to commissions for Cancún Underwater Museum (opened 2010) off the coast of Mexico, Museo Atlantico (2016) in Spain’s Canary Islands, and the Museum of Underwater Art (2019) in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Taylor’s works divert visitors from fragile natural reefs and provide artificial habitats to support underwater life. Usually depicting people engaged in everyday above-water activities, the sculptures change as they become a home to ocean life. In addition to his large-scale projects, his submerged statues can be seen in Greece, England, Bahamas, and Indonesia.

Karen Russell is a celebrated fiction writer known for her feverish blends of the supernatural and everyday. Her accolades include a Pulitzer nomination, a MacArthur “Genius Grant,” and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Russel was raised in South Florida, the setting of her 2011 novel Swamplandia!, a Pulitzer-nominated story about a family of alligator wrestlers. The novel grew out of a short story in Russel’s debut collection, St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves (2006), written while completing her MFA at Columbia University. She has since released two more collections: Vampires in the Lemon Grove (2013) and Orange World and Other Stories (2019). Her stories have appeared in The Best American Short Stories, Granta, and The New Yorker, among other places.

Russels’s work straddles genres, spanning fantasy, science fiction, horror, and literary fiction, as in her novella Sleep Donation (2014), which presents a nightmarish version of America where sleep deprivation has become a national epidemic. She teaches creative writing at Texas State University and lives in Oregon.

Segments

- Literature

- Stage & Screen

- Literature

- Art & Design

Transcript

Welcome to Articulate, the show that explores how really creative people understand the world. And on this episode, Arthur Yorinks has been the power behind the throne for many of America’s most significant artists over the past 40 years and he’s very comfortable with this role.

Arthur Yorinks: I’m a pretty insecure guy but when I’m in a room by myself and working, I trust what I’m doing.

Tori Marchiony reports on how Karen Russell’s stories live in the space between the every day and the surreal.

Karen Russell: I’m like okay, from the point of view of a horse on the moon, now we can talk.

And Jason deCaires Taylor’s greatest assets are under water. All of his sculptures have been entrusted to the oceans.

Jason deCaires Taylor: I do feel some attachment but there’s also really sort of liberating feeling then. It’s like having children, they’re free, you set them free.

That’s all ahead on this Articulate.

For many writers, storytelling is, by choice, a solitary act. Not, though, for Arthur Yorinks. He’s been a go-to partner for many of modern America’s most renowned artists across a variety of genres. A libretto for a Philip Glass opera, a dance for the American modern company, Pilobolus, audio plays featuring Sigourney Weaver and Frances McDormand, picture books with Mort Drucker, David Small, and Maurice Sendak. Today, Yorinks lives in bucolic bliss on a farm in Upstate New York. He is a gifted storyteller, but one who has never craved the spotlight. The fact he discovered as a prodigious pianist, age seven.

Arthur Yorinks: I’m playing, practicing, all of that. I’m really enjoying it, loving it, it’s for me. And then company comes over and my mother says…

AJC: Perform.

Yorinks: Perform. And I hated it. To this day, I could feel right now that feeling of, don’t look at me, I don’t want to do this. You’re not interested. And so, I became even more shy about that kind of stuff.

Yorinks gave up the piano when he was 16. He decided his future lay in writing when one evening he became immersed in a book from his father’s vast collection.

Yorinks: My father was an odd, by himself kind of guy, but he was an avid reader. But when I watched him read, I thought he looks like he’s having so much pleasure, that I emulated that. There were no kids books, oddly, in the house. I mean, there was maybe a set of Graham or Anderson, but no picture books, nothing like that. I didn’t even know what those were. So, here I am one night and just my large Standard Poodle and I were in the house, I mean for an hour or two. So, I took out Poe and I started reading it and I, you know, it was a story called The Black Cat and I remember this exactly, I stopped, ’cause I was getting scared and then I said, wait a second, this is just words. Somebody wrote this down. What kind of power is that? That somebody puts words together and I’m freaking out here. You know almost climbing under the bed with my dog. I want to be able to do that. And that was it for writing. I mean, I knew that whatever I did, in addition to whatever all the things I did, I wanted to be a writer.

And write he has. Despite the dearth of children’s books in his family home, the adult Yorinks has mastered the form with 39 books published to date, including 1997’s Caldecott medal winner, Hey, Al. Yorinks’s characters don’t talk down to kids, they tend to sound like adults with vivid imaginations and there’s a good reason for that.

Yorinks: I kind of channel, believe it or not, this is gonna sound very strange, the innocence of my mother and my father, they had a similar odd, coming from very different angles. I recall sitting on the stoop of the house and my mother going on and on about life on other planets and the dreams that she had which were quite vivid and fantastical. On the flip side, my father would be known to sit at the table and just start talking, nobody, not directing it to anybody and just was telling a story and it happened to be something that he read or something, but he didn’t care that nobody was listening to him. Except I always listened to him. And so, that not only enabled me, but engendered in me a constant curiosity and that curiosity of asking a question is what I think is a part of childhood. Kids are always trying to figure things out. You know, we’re all, well we’re always trying to figure things out. And what I do when I’m in that mode of writing those books and I never think of them, of course, as writing for kids, so they’re just books to me, of answering questions. And I don’t put limits on the answers. I honestly think if a guy works in a butcher shop and he’s surrounded by meat all the time, his dream would be to turn into a fish. I don’t censor those…

AJC: Or question whether

Yorinks: No question.

AJC: it’s gonna work or not.

Yorinks: That’s right.

AJC: That’s a lot of self-trust.

Yorinks: I’m a pretty insecure guy but when I’m in a room by myself and working, yeah, I do trust what I’m doing.

But Yorinks has often been overshadowed by his collaborators. Perhaps none more so than the legendary illustrator, Maurice Sendak. In 1970, the 42-year-old Sendak was already world famous for Where the Wild Things Are when a 17-year-old Arthur Yorinks and a friend knocked on his door.

Yorinks: And the door opens and there’s Sendak. And clearly, he was like, who are these two kids? And I said something, like the exorcist, words were coming out of my mouth, I had no idea what I was saying. You know, I admire your work, the typical bologna. He was very polite, he didn’t open the door and let us in, but he just said, “Look, I’m in the middle of a book. If you’d like to talk, I’d be happy to talk to you on the phone.” And it was very cordial, nice, all of about three minutes. So, door closes, we go off. And then comes the dilemma. Every month or so, I would dial his number, rotary dial, no caller ID. “Hello?” Click. I, yeah, it was terrible. I did it like four times. Now I had a Standard Poodle which I mentioned earlier. The odd thing about this dog, she never barked. Dialing Maurice, “Hello.” I was so distracted, I thought, “Oh my God, I’ve never heard this dog bark.” And all of a sudden, like in the cartoons, you know, hello, hello? And it’s Maurice.

AJC: Speech bubbles are coming out of the phone.

Yorinks: And I, then this is totally, again, ridiculous. He’s gonna know it’s me, I can’t hang up now. So, we had a conversation. And the conversation was basically a disguised interview, of course. What do you do, what do you blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And it was met with, and I’m trying to lie, I’m trying to make up things. You know, “How old are you?” “I’m 17.” Oh, oh. You know, I mean, at every moment, and I don’t think that fast so, I’m just spurting out the truth. So, he gets to the last question, which I didn’t know was the last question. He says, “Have you ever read Winnie the Pooh?” “Yes, I’ve read it.” “What did you think?” And I thought, what does he want to hear, what does he want to hear, what does he want to hear? And as my brain is saying that, the words come out of my mouth, “Oh, I hated that book.” There’s a pause. I, you know, after all this, I just said the wrong thing and as I’m thinking that, he says, “Why don’t you come over for lunch on Tuesday?” I said okay. So, I went to his house on Tuesday. I had a tuna fish sandwich and a ginger ale on his little patio in the Brownstone. We talked and though we had this disparity in age, generation, whatever that is, we were very similar. So, we hit it off. We hit it off, we became good friends. Unlike what a lot of people think of Maurice as a kind of a morose and serious guy, of which he was, he was—

AJC: And grumpy.

Yorinks: And grumpy and, you know, but he was absolutely hilarious and that was the thing we shared, humor.

For years, Yorinks and Sendak avoided working together. They didn’t want to mix friendship and business. But in 1992 they broke their pact by founding a children’s theater company in New York City called Night Kitchen, which they ran as partners for nearly a decade. During that time, they also wrote their first kids book together, The Miami Giant. Their fifth, Presto and Zesto in Limboland was released in 2018, six years after Sendak’s death. Without his dear friend and collaborator, Yorinks has had to go at it alone again to write a stage adaptation of Where the Wild Things Are. It premiers at the New Victory Theater in New York City in the Fall of 2020. As always though, Yorinks would like to stay in the shadows.

Yorinks: I wrote this thing with the intention that when people see it, the book has only 300 words or something like that, so obviously I had to make something up, but my goal was that, oh, did Maurice leave this play laying around?

It’s a plausible scenario. If Maurice Sendak had left behind an unrealized play, he might well have counted on his friend, Arthur Yorinks, to get the job finished.

Karen Russell is most at home in made up places.

Karen Russell: I feel so much more comfortable in fiction. I feel like that’s the only place where I can be honest about certain things. I’m like, okay from the point of view of a horse on the moon, now we can talk. I have to go quite a distance, I think, from my own perspective.

And Russell’s imagination has taken her far. Her debut novels, Swamplandia! about a family of alligator wrestlers in the Florida Everglades put her in a three-way tie for the 2012 Pulitzer. The next year, she won a MacArthur genius award. Russell is celebrated for her ability to make the strange seem inevitable in stories about everyday life. An epidemic of nightmares that create an entire society of insomniacs. A support group for new mothers who’ve agreed to nurse a demon. A pack of children brought up by wild animals who were taught civility by nuns. Even mythological creatures lurking among citrus trees.

(Excerpt from Vampires in the Lemon Grove)

When we first landed in Sorrento, I was skeptical. The pitcher of lemonade we ordered looked cloudy and adulterated. Sugar clumped at the bottom. I took a gulp and a whole small lemon lodged in my mouth. There is no word sufficiently lovely for the first taste, the first feeling of my fangs in that lemon. It was bracingly sour with a delicate hint of ocean salt. After an initial pickling, a sort of chemical effervescence along my gums, a soothing blankness traveled from the tip of each fang to my fevered brain. These lemons are a vampire’s analgesic.

Though it might seem that being a novelist would offer some great vacation from reality, for Russell, even the most outlandish stories come from a deeply personal place.

Russell: I often think sometimes that fiction is more frighteningly revealing to somebody about somebody than nonfiction, ’cause if you’re writing under the spell of your own name and like let’s say it’s an op-ed or something, you’re sort of, I’m gonna stake out this position, I’m gonna defend it. In a story where anything can happen, it is a little bit like being in a dream, and in the same way that dreams will reveal things that you’re maybe uncomfortable knowing, because you’re just the hostage inside your own body and you’re having this very honest communication that you’re not really mediating in any way, frighteningly, it can feel like that. I just find like, particularly with stories, I’ll be like, this is gonna be a totally different story. I’ve never written anything in this landscape. Different point of view, new characters, whole new people, and then you’re sort of like, oh this again.

AJC: Here I am again.

Russell: Here I find myself, right.

One recurring theme in Russell’s work is how the supernatural strides almost imperceptibly in step with the seemingly mundane. It’s a gift she traces back to her childhood, set in the unpredictable environment of southern Florida.

Russell: Speaking of an incubator for an imagination, I mean, I think the weather plays such a role there and nature, the humidity is part of it but there’s no way to think of your life as separate from this animal world because it’s just embracing you. You’re sweating into it, you know, it’s just the membrane that you’re moving through is reminding you that you’re in the tropics, really. And the weather’s always changing, I mean that’s something really unique about South Florida. You’re always in peril too, there’s like a cheerful amnesia for most of the year and then it’s hurricane season and everybody remembers that they’ve chosen to live on sand at the edge of the continent. And where there are lizards in your bathtub and none of that seems so unusual if you’re a kid, but then maybe later, in retrospect, you’re like, that’s interesting.

Karen Russell is now experiencing another childhood. This time, set in Portland, Oregon where she and her husband are raising their growing family. Her latest collection, 2019’s Orange World is named for a short story about the overwhelming worry that accompanies parenthood.

(Excerpt from Orange World)

“Orange World,” the New Parent’s Educator says, “is where most of us live.” She shows a slide, a smiling baby with a magenta birthmark hooping her eye. No, a burn mark. The slides jump back in time to the irreversible error. Here is the sleepy father holding a teapot. Orange World is a nest of tangled electrical cords and open drawers filled with steak knives. It’s a baby’s fat hand hovering over the blushing coils of a toaster oven. It’s a crib purchased used. “We all make certain compromises, of course. We do things we know to be unsafe. You take a shower with your baby and suddenly…” The educator knocks her fist on the table to mimic the gavel rap of an infant’s skull on marble. Her voice lowers to a whisper to relate the final crime. “You fall asleep together on the sofa. Only one of you wakes up.” Don’t fall asleep, Rae dutifully takes down. Orange World.

But for all the anxiety that motherhood has brought with it, Russell says her son has also added a delightful new kind of strangeness to her life.

Russell: Time moves in such a different way now, it’s really uncanny. He really changes every second in a way that makes me very aware that I’m living in the present. And sometimes, if I’m with him there are not as many rooms to go to. I just feel like I have to be present with him and that’s a real gift because not since my own childhood have I felt so kind of riveted to my skin and in my body and in this world, with him. You know, I think a lot of my adult life, obviously has been spent in sort of imaginary realms, but also just in like the boring places we all go. And sometimes it can feel very claustrophobic not to have this space to kind of reminisce and daydream and whatever. There’s something about just like blowing bubbles on the floor in real time that reminds me so much of being a child myself, when everything had that sort of heightened reality because that was it. This is like the first tree you know, so you’re really attending to it. I mean, we have been taking birds for granted, for example. We have to greet every bird in the sky. It does restore a kind of wonder. You have permission again or something to, yeah, you remember a little bit.

Karen Russell chooses to see what so many of us habitually ignore. The weird, the fantastical in the everyday and her stories invite us to see the world that way too.

Though many of us are quick to forget it, we are entirely dependent on water. Or that half of our bodies are made of it and two-thirds of our planet is covered by it. Yet somehow it remains mysterious.

Jason deCaires Taylor: You know, I think we’re so connected to water and I think it’s intrinsic in us.

Jason deCaires Taylor is a pioneer of underwater sculpture parks. Elaborate destinations designed to support and nurture coral reefs, sometimes by luring tourists away from more vulnerable areas, always by inviting new life. This, deCaires Taylor says, is the kind of impact he first had in mind when he set out to become an artist so many years ago.

JDT: I studied public sculpture in London. I had quite a few exhibitions in public spaces and I kind of always left with a sense of sort of futility that you invested so much of your heart and soul into making these things and then at the end of it, we store them, pack them away and we’re just sort of creating more stuff for the planet. Subsequently, I became a diving instructor. I dived in different countries around the world. And then I sort of caught on this idea that, actually, if I made these permanent underwater works and cited them in the right type of environment, then actually that besides their artistic value, they would also become a habitat space, they would help sort of rejuvenate areas of underwater sea bed.

deCaires Taylor’s work has taken him from Oslo in Norway to Cancun Mexico to the Spanish governed Canary Islands. During his time there, he created a vast underwater installation called the Museo Atlántico. Among its 300 sculptures, the Raft of Lampedusa attracted much attention for its depiction of African refugees.

JDT: The Canary Islands had been a stepping stone into Europe for many, many years and they have a very long history of the migrant route. So, I wanted to recount some of the history of the island and a lot of the people that are actually in that installation were migrants who had come over to the Canary Islands who had started new lives and were very successful. But it also obviously coincided with the huge crisis that was unfolding in the Mediterranean at the same time.

Wherever Jason deCaires Taylor goes, nature is his humbling co-creator. But though hundreds of hours of craftsmanship will quickly be claimed and rewritten by the ocean, he has few qualms about surrendering his sculptures to the sea.

JDT: I do feel some attachment, but there’s also a really sort of liberating feeling that, it’s like having children where you, they’re free, you set them free. And for me, I love going back and watching how they’ve changed, how they’re evolving, you know that, for me, is much more interesting than the original work in itself.

AJC: You live in a world of unforeseen circumstances. Many positive, any negative? Have there been times where you’ve thought, oops, need to go back and fix that or we didn’t think we were gonna have a destructive effect or?

JDT: Definitely, I mean, they’re under water. It’s very, very hard to predict what’s gonna happen. Obviously, we endeavor, we do a lot of research and a lot of testing and consult many different local operatives, but it’s a very changeable space, a very dynamic space.

AJC: You once, was it in Cancun, where you created an area and lobsters showed up and the lobster fisherman showed up about 10 minutes later, did I read that somewhere?

JDT: Yes, so, I made some lobster habitats in Cancun and they’re amazing. We had a couple hundred lobsters and I was sort of cooing about it one day and the next day a fisherman went down at night and had the lot and they were on the Hilton buffet. Yeah, I mean also the changes, sometimes I go down and expect to see sort of vibrant corals and sponges and I go there and there will just be like a black sludge that’s adhered to it or I’ve been down another time where I made 200 sculptures and they were just slowly sort of changing and they had these sort of coralline algae forming which was a really good sign. And I was like excellent, they’re really working and then a week later I went and they were just completely inundated with this thicket of sargassum seaweed and they just look like a giant bush or a giant forest, I was really alarmed by that. That was the one time I was kind of quite disturbed.

AJC: Could you fix it, or did you want to?

JDT: Well it’s interesting. We did a test, so we actually cleaned off, the sargassum on around 20 of the sculptures and stripped them back to their natural state and then I went back like four months later and the ones that we cleaned were then covered again in the thick algae and the ones we’d left to their own devices, they were actually perfect. All the algae had been eaten by the fish, it had been kind of washed off by the tides and I think that was the main sort of point where I realized that just leave it alone, from that point of installing it, it’s just best to let everything take its course.

Though he knows it’s impossible to micromanage the ocean, deCaires Taylor and his team do put great thought into how they can positively influence outcomes. The sculpture parks are custom designed for each site and because coral can take hundreds of years to form, the sculptures are made of super durable concrete that actually hardens under water over time. The surface of every sculpture has a neutral pH to avoid contaminating existing life. But textures vary depending on what type of growth is being invited. And he’s getting pretty good at it. deCaires Taylor’s latest project brought him to a wonder of the natural world: Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. In fall 2019, he installed a massive greenhouse designed to protect the reef from further damage from rising sea temperatures. Jason deCaires Taylor believes he has found his life’s purpose helping to rectify some of man’s damage to the underwater world.

JDT: I think art has a responsibility. I think our world is changing so rapidly. There’s so many burning issues. There’s so many fundamental things that are happening now that if I produced anything that didn’t talk about these things then I would feel it was very pointless.

Instead, deCaires Taylor casts his life’s work to the ocean floor hoping that what he leaves behind will improve life for all of us.