The Search for Better Worlds

Description

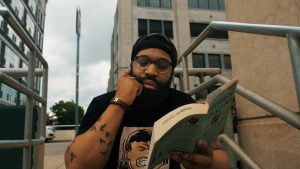

Writer Tochi Onyebuchi imagines worlds that never were, but always grounds them in this one.

Featured Artists

Tochi Onyebuchi is an award-winning science fiction writer and former civil rights lawyer.

He was born in 1987 in Northampton, MA, to Nigerian parents, and raised in Connecticut. Onyebuchi earned a BA in political science at Yale University, an MFA in screenwriting at New York University, a master’s at L’institut d’études politiques in France, and a law degree from Columbia Law School.

He began writing novels while still in high school and published his first book, the young adult novel Beasts Made of Night, in 2017. Set in a fantasy world based on Nigeria, the work won the Nommo Award for African speculative fiction and spawned the sequel Crown of Thunder (2018).

Onyebuchi’s first adult novel, Riot Baby (2020), tells the story of a wrongly imprisoned boy born around the time of the 1992 Los Angeles riots and his supernaturally powerful sister. It was nominated for a prestigious Nebula Award for science fiction.

Transcript

As the child of Nigerian immigrants, Tochi Onyebuchi has always wrestled with his identity as a Black American.

Tochi Onyebuchi: Oftentimes, I’ve felt like an interloper in the African-American experience even though all these external cues are lumping me into that same bucket so, you know, my parents didn’t live through the Detroit race riots. There’s no real, you know, historical, you know, lived tangible connection between me and the civil rights struggle, but I benefit from these things by virtue of my color. And so, when Black Panther comes out and it’s cool to be from Africa, you know, I get to walk around with this privilege.

That ambivalence has manifested in his writing. From an early age, Onyebuchi wanted to be a storyteller and would grab at any chance he got to write, but it wasn’t until he was in his mid twenties that he included characters who looked like him in his stories.

Onyebuchi: It was the very first time that I wrote Black main characters. The very first time in my entire life and writing career. I just wasn’t imbibing, particularly, speculative fiction wherein people who looked like me were the main characters. It just like wasn’t, it wasn’t readily available to me.

Born in Massachusetts in 1987, Onyebuchi was the oldest of four children but his adolescence was cut short the day before his 11th birthday, when his father died of cancer. Onyebuchi’s mother began working multiple jobs to provide for her family. He felt obliged to help ease her burden, but that sense of responsibility held him back from his own grief. He was diagnosed with depression in high school and later with bipolar disorder. He started drinking heavily and became what he’s described as a raging alcoholic. He was in his mid twenties when he quit, but all the while he was somehow also nurturing his writing. Onyebuchi was especially drawn to the escapism of speculative fiction of science fiction and fantasy.

Onyebuchi: You can have work that’s so busy, there’s so much going on. There’s not just the story that you’re reading on the page. There are all these other levels and allusions and whatnot that you can unpack. And that’s something that I also really, really, really appreciate about science fiction and fantasy. You can live with a book. Any free time that I had, I was writing. If I had a free period in the middle of the day, I was writing. If I finished my homework early into study hours, I was writing until lights out. On the weekends, it was an absolute boon, you know. I didn’t go out to parties or things of that sort, you know, a terrible amount ’cause I was always busy writing. And the thing about it was, I didn’t… I never felt as though I was missing out because I loved writing so much.

By high school, Onyebuchi estimates he was already writing a novel a year, 16 of them before he ever got published. But storytelling, he surmised, could never be a career, rather something he squeezed in around a real job. And so as he began law school at Columbia, he realized that he wasn’t just stealing time to explore his ideas. His studies were helping to expand them.

Onyebuchi: It was in law school that I really got immersed into the issues of incarceration, both overseas and in the United States, and that changed my life. The African-American experience was very much an academic item in my life but then, like I started knowing people who went to jail. I started personally knowing people who went to prison. I started personally knowing people who got sort of chewed up and spit out by these systems and you know, it…that made it real in a way that it wasn’t necessarily real for my parents’ generation.

Onyebuchi’s legal training became a tool kit for him to dissect increasingly complex realities through increasingly complex fiction. In the years that followed, as public awareness of police killings of African-Americans grew, so too did Onyebuchi’s need to make sense of it all.

Onyebuchi: I knew that there was something sort of maybe poisonous, sort of festering in me. It was this combination of rage and hopelessness and so many other things, but I knew I needed to get it out of me. I knew I needed to expel it somehow and the way that I organize the universe is through writing that’s how I’m able to sort of articulate so much and when you can sort of articulate the shape of the monster before you, it all of a sudden becomes a lot less intimidating.

Riot Baby was the outcome of that articulation. The book follows two black siblings: Kevin who becomes imprisoned, and his sister Ella who has supernatural powers.

Onyebuchi: I didn’t necessarily see a protagonist who was a young black woman who basically, you know, had the powers of a God. I’d never seen that before. And, you know, growing up in South Central surrounded by gangbanger culture, living through the Rodney King uprising, you know, being in Harlem during the 2000s and developing this, developing this incredible power. But being incredibly angry at the same time and trying to figure out where that anger is coming from—that was very compelling to me. There’s almost a sense of Greek tragedy to it where, you know, you can do whatever you want, essentially, with these powers except for this one thing. And it’s the one thing that you want more than anything to be able to do, which is protect your younger brother.

Riot Baby was a finalist for the Hugo and Nebula Awards, two of the highest honors in speculative fiction. But fantasy writing wasn’t just a way for Onyebuchi to connect to massive political struggles. It also helped him to grapple with something more intimate, his own family’s tangled history. Onyebuchi’s mother grew up in Nigeria during the Biafran War. After hearing about her experiences, he wrote War Girls, a novel set in 2172 which follows a similar civil war.

Onyebuchi: I had heard in an off-hand comment as we were driving back from some family friend’s place during some holiday season, Mom mentioning having to live in the forest for a period of time with her family, just an offhand comment and then we were talking about something else. And I was like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa! Hold up a second, can we like rewind?” And she went into this whole, you know, story about being an internally displaced person in Nigeria during the civil war, which started right after she’d finished kindergarten. There’s this question that I ask myself or at least asked myself during the composition of War Girls was, you know, “By forcing my mom to excavate these memories, am I re-injuring her?”

AJC: Did you ask that question as you are asking for the stories?

Onyebuchi: Yes, I asked my—

AJC: And she tutted and said “I’m made of sterner stuff, son”?

Onyebuchi: Well, she is…I mean, she’s incredibly stoic, right? And it, you know, part of that is the, you know, completely living into the immigrant stereotype of, you know, you just sort of keep it moving. You don’t let anything stop you. You do all these impossible things so that your, you know, your children and their children can have the much better life and it’s the American dream, right? So she was very stoic about all of it and very, you know, very generous with her time and with her memories and things of that sort. But I could not help this sort of creeping guilt that I was putting her through something or that, you know, to a certain extent that I might’ve been causing her any sort of pain.

Still, Onyebuchi worked through any guilt he felt. War Girls wasn’t only a chance for him to write about his mother, but also to write with her.

Onyebuchi: What was actually really meaningful was at a certain point towards the end of the writing of the book, I had to submit a pronunciation guide to Razorbill. And so, I went through with mom over all the words that they had questions about and she recorded pronunciations for them. And, you know, even looking back on that memory now I have to like, you know, I have to control my emotions a bit because it seemed like in many ways, the culminating moment of what I’d been trying to accomplish with this book, personally, which was to get closer to mom. It just felt like there was this abiding love, ’cause it also felt like…it also felt like validation of my career choice. So there’s that aspect of it too where, you know, she’s helping me be a writer, she’s helping me write a thing.

Tochi Onyebuchi has navigated his life by latching onto the core tenet of science fiction and fantasy: oftentimes, to understand the world better, we have to create and explore new ones.

Onyebuchi: As human storytellers, I don’t know that I’ve come across a story yet where there isn’t that connection, I don’t know that we’re capable as human storytellers of getting to a place where we inhabit a completely alien consciousness that is completely devoid of human experience or emotion or any sort of linkage to our lived experience.

Tochi Onyebuchi fills his stories with magic, telekinesis, space colonies, and cyborgs. But under-girding it all is a voracious curiosity to connect how and why people behave as they do in a world that can seem unrelenting, unpredictable, and unfair. And while he hasn’t found answers to all of his questions, he’s dedicated to creating vast new worlds where he just might.