The Trailblazer

Description

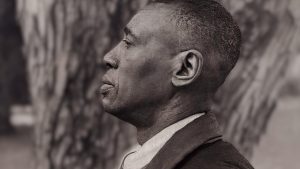

Horace Pippin was one of the early 20th century’s most important African American artists. A veteran of the Great War, he found healing and renown in painting and blazed a trail for those who would follow.

Featured Artists

Horace Pippin (1888–1946) was a revered artist, known for his paintings depicting war and the African American experience, including slavery, segregation, and daily life.

Pippin was born in West Chester, PA, and grew up around Goshen, NY. As a child, he won a set of crayons and paint in a magazine contest and drew pictures of horses and jockeys at a local racetrack. He served in France during World War I, sustaining permanent damage to his arm after he was shot in the shoulder by a sniper.

He took up painting in the 1920s to rehabilitate his injured arm and completed 140 canvases in the fifteen years before his death. Admired for their heavy application of paint and restrained use of color, his artworks were championed by major collectors and galleries in the late 1930s, and famously featured in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1938 exhibition “Masters of Popular Painting.”

There have been three major retrospectives of his work, in 1977, 1994–1995, and 2015.

Transcript

The American painter, Horace Pippin, created some of the most important yet underappreciated works of the 1930s and 40s, but when he first picked up a brush, it was without serious ambitions. He only began painting to help rehab a shoulder injury he had sustained in the trenches of World War I, but it didn’t take long for Pippin’s simple, emotive style to capture the attention of a world hungry for new perspectives.

Martha Lucy: I think we should call him an American painter. I mean, yes, he painted African American subjects, but he’s just as important as any other American painter, so I don’t really see why we have to make that distinction.

Audrey Lewis: He has interest in social issues like racism, and the effects of the war, and that is expressed in his painting. Sometimes subtly, and sometimes more obviously.

Gwendolyn Dubois Shaw: This is a moment that is very focused on what is American, and how can the United States differentiate itself from Europe.

Previously a senior historian at the National Portrait Gallery, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw is now an associate professor of art history at the University of Pennsylvania.

Shaw: Europe is seen by many American scholars during this period of the 1930s as a kind of older, decrepit, dying culture. One that has run its course, and has ended in the enormous conflagration that is World War I. And that Americans, if they’re going to move forward, need to find something in their own culture that is not derivative, that is truly American.

Horace Pippin was born with a strong creative impulse. As a kid, he won his first set of crayons in a magazine contest, and fell in love with drawing pictures of horses and jockeys at the local racetrack. Years later, Pippin would use art to help process the horrors he witnessed as a young soldier during World War I fighting with the famous Harlem Hellfighters, the first predominantly black unit in the U.S. Army, and not uncoincidentally, the longest serving U.S. regiment on the front lines.

Lewis: He illustrated a journal with the story of his time in France. Very descriptive, probably done after his return from there. But it’s very interesting in terms of telling the suffering that he saw, and also just the day-to-day activities of soldiers in the trenches, wearing gas masks, marching through no man’s land. And he tells the story very simply, but beautifully, and the illustrations reflect that.

Audrey Lewis is a curator of the Brandywine River Museum of Art on the Delaware-Pennsylvania border. She put together the first major Pippin retrospective in more than 20 years, “Horace Pippin, The Way I See It.” Pippin was born nearby in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and returned there as an adult. Many of his paintings depict daily life in that bucolic town.

Lewis: He portrayed singers on a street corner, it’s called “Harmonizing,” and there’s four men singing together on the corner. There is another scene in West Chester just called “West Chester,” and it’s a scene of what looks to be row homes that are very similar in appearance to his own home. He was drawn to that, probably because he was just interested in his local community. The West Chester courthouse is still standing, and he was attracted, I think, to it for aesthetic reasons. The brick, the red brick was something that he was attracted to in a number of paintings. I think he liked the play of the trees against the brick.

Artists in West Chester championed Pippin’s talent, including the celebrated illustrator N.C. Wyeth, who gave him his first solo show in 1937. Before long, small town enthusiasm had snowballed into national fame. Pippin caught the eye of the Philadelphia art dealer Robert Carlin, who gave him another solo show in 1940. Soon after, the famously prescient collector Albert Barnes, noted for acquiring works by prominent early 20th century European artists while they were still alive, began buying Pippin.

Lucy: He saw Pippin as somebody who represented real America. He called him distinctly American, and he called him the first great African American painter.

Martha Lucy is deputy director for research interpretation and education at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. The collection displays the eclectic range of Barnes’ interest, and the unique logic he used to draw connections between them.

Lucy: He also, sort of interestingly, likened Pippin to African American spirituals. This music that Barnes was completely just so excited by, and he sort of saw it as the visual equivalent of that music, which he also talks about in terms of its starkness, and its emotion, and its simplicity, and all of that stuff is part of this idea that artists who haven’t been trained are more authentic.

This idea is central to the label of outsider artist, a category whose very name reads like a backhanded compliment. The term has been applied widely, sometimes referring to artists without formal training, with a mental or physical disability, or with those who simply eschew art world norms. And while Pippin didn’t have formal training, or perfect mobility in his right shoulder, what really made him an outsider was his attitude.

Shaw: These outsider artists, they’re working for themselves, they began to create for themselves. Pippin starts in part as physical therapy, but also because he wants to create images. So for him, it’s a very personal experience. He’s not making art early on to support himself, he’s not making art to become famous, he’s not creating art to impress others.

Horace Pippin remained self-determined throughout his life, even as he received mixed messages about his art. While Albert Barnes claimed to admire that Pippin’s approach to painting was untainted by formal education, the collector still attempted to bring the artist into the fold, inviting him to study at the Barnes Foundation, but the impact those few months of lessons had on Pippin’s signature style is debatable.

Lucy: His palate does become brighter, and he’s sort of playing with new color juxtapositions. And Barnes loves to say, “Oh, he’s been looking at Matisse, and you can see it in his work.” I don’t know if we can say that, but Barnes certainly made that connection.

Lewis: He remained independent, despite all of those influences, focused on his own vision, and he in fact said something to that effect when Albert Barnes was trying to urge him to paint a certain way, and Pippin said, “I don’t tell you how to run your foundation, so let me paint the way I want.”

AJC: Wow.

Lewis: I’m paraphrasing, but that was basically the message.

AJC: Speaking truth to power.

Lewis: Yeah.

Indeed, the fiercely independent spirit that gained his work so much regard within the art world could sometimes come across as disrespectful to those who were deeply invested in the way things had always been done.

Shaw: He doesn’t seem to care about fashion, and there are these wonderful anecdotes about him that says that he doesn’t really care about the art world in some ways. When he goes to Chicago to have his work displayed at the Art Institute, and he’s showing at the same time that Salvador Dali is, and they run into each other in the galleries to be introduced, and Pippin says to Dali, “Oh, are you an artist, too?” And Dali is mortified, absolutely mortified, and he is just so offended that this man doesn’t know who he is, that he leaves the building, he leaves the opening, and Pippin just doesn’t understand. Pippin sees painting as a regular thing that regular people do, and not as something that’s rarefied or celebrity informed.

Lewis: He was in his forties when he first gained acknowledgement. He was an artist who spoke from the heart, personal paintings about his own experience, but he also made subtle commentary on social issues, such as racism and religious issues. So his work carries over into many different subjects, and I think that his appeal is to people who may respond to his expressiveness, his kind of soulfulness, and his very evident bearing of his self.

Shaw: For me, the most powerful and important piece by Pippin is the image of John Brown on his way to his execution.

The abolitionist John Brown was sentenced to be hung to death after his attempt to start an armed slave revolt by raiding the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry in 1859. Though the raid failed, the incident is often cited as a catalyst for the Civil War.

Shaw: We see Brown sitting in the back of a buckboard wagon, being driven by soldiers to his execution. And Pippin shows Brown passing through the city, what is now Charlestown, West Virginia, in front of all of these people, and most of them, all of them are really turned towards the wagon, except for this Black woman who stares out at us. And this is Pippin’s grandmother, right, we’re told this through stories from Pippin. It’s the kind of the great legend of Pippin’s grandmother at John Brown’s execution. And she looks out at us addressing us, right, directly at the viewer. We see this great historical moment that’s so pivotal, and Pippin makes it personal. There are thousands of images of John Brown, hundreds of paintings and representations that flood the market after his death, and he becomes an icon of abolitionism, of kind of the great white abolitionist who’s willing to sacrifice his life, and that of many of his children, for the cause of freedom for Blacks. Pippin makes it personal, he puts his grandmother there. He makes it part of his story, he makes it part of his family’s story, and in doing so, I think he really makes it part of all of our stories, and that-

AJC: And she’s looking at us and saying-

Shaw: She’s looking right at us.

AJC: What are you prepared to do?

Shaw: Exactly.

AJC: Is that what she’s saying?

Shaw: What are you prepared to do? I was here. You could have been here. Could this have been you?

Pippin’s paintings traveled widely throughout the 1940s, to New York, San Francisco, Chicago, but the artist maintained a fairly normal life at home in West Chester with his wife, Ora Jennie, until in the mid 1940s, she suffered a nervous breakdown and was institutionalized. Pippin tried to fill the void with alcohol, which is believed to have contributed to his untimely death in 1946, at the age of 58. “Man on a Bench,” set in the town where he was born and died, was among his final paintings.

Lewis: And that has been immortalized in the town. They have erected a bench, painted it red, in his honor. That painting is kind of iconic. It’s been interpreted different ways, one of them being that it’s a symbolic self-portrait.

AJC: How so?

Lewis: In that the person looks lonely. And this is late in his career when there were personal issues that were arising in his life. His wife’s mental health had deteriorated, and that was a great cause of concern for him, that he’s having a difficult time painting because of that. And this painting evokes that kind of loneliness.

Horace Pippin’s career was short-lived, due to his late start and early death, yet the works he managed to produce have secured his place in the pantheon of great American artists. Today, reflecting on what he was able to accomplish against the odds begs another question: what could he have been had the odds been in his favor?

Shaw: What if he had lived in an integrated society? A society that recognized that all of its children should have access to art lessons and training. What if that little box of crayons that he won in a competition as a very young child, what if there had been more than that, right? What if he had been given access to classes, to art classes? If he’d been encouraged, if he’d been able to pursue his art from a really young age, as opposed to kind of taking it up later in life? What could we have gotten from him as an artist? What sort of a career could he have had?