The Unconventional

Description

The unconventional paths of Heidi Latsky, Gary Baseman, and Bang on a Can.

Featured Artists

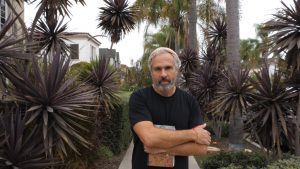

Gary Baseman is an esteemed artist known for his distinctive characters and cartoonish style. His work has been exhibited in museums and galleries throughout the world and is featured in the permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the National Portrait Gallery.

Baseman was born in Los Angeles in 1960 to Polish Jewish Holocaust survivors. After graduating from UCLA, he worked in New York as a commercial illustrator; his projects included the design for the popular board game Cranium.

Returning to L.A., Baseman moved into fine art with the exhibition Dumb Luck and Other Paintings About Lack of Control (1999). His career retrospective Gary Baseman: The Door is Always Open premiered in Los Angeles in 2013 and traveled to Taiwan and China.

Baseman’s illustrations have appeared on the cover of The New Yorker and in the pages of many magazines. He won an Emmy Award for his animated series Teacher’s Pet (2000–2002) and in 2014 created Mythical Creatures, an animated documentary designed introduce the stories of the Holocaust to new generations.

Heidi Latsky is a groundbreaking choreographer known for incorporating disabled performers into her dance pieces.

Raised in Montreal, Latsky began dancing seriously while a student at Carleton University in Ottawa, at first in disco dancing contests. She moved to New York in the 1980s and performed as a principal dancer for Bill T Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company from 1987 to 1993. From 1993 to 2000 she toured with dancer Larry Goldhuber as Goldhuber and Latsky, before founding her own company, Heidi Latsky Dance, in 2001.

In 2006, she received a commission from disabled dancer Lisa Bufano to choreograph a 25-minute solo piece. This inspired Latsky to put her company at the forefront of physically integrated dance with such works as GIMP (2008), a dance-theater piece for four conventional dancers and four performers with physical disabilities. Her live art installation On Display (2015) and art film Soliloquy (2017) also integrate disabled dancers.

Latsky advocates for disability rights, serving on a working group for the New York mayor’s office and a consultant for New York University, among other roles.

Bang on a Can is a New York–based contemporary classical music group best known for its daylong Marathon Concerts.

The organization was formed in 1987 by married couple Julia Wolfe and Michael Gordon and their friend David Lang; all three were graduates of the Yale School of Music’s composition program. Created with the goal to break down traditional boundaries between musical genres, Marathon Concerts present a range of contemporary classical compositions in an informal atmosphere, with guests free to dress how they like and come and go as they please.

All acclaimed composers in their own right, Gordon, Lang, and Wolfe have composed several staged works jointly as Bang on a Can, including The Carbon Copy Building, a “comic book opera which won the 2000 Obie Award for Best Production. The company has also commissioned and premiered pieces by numerous other composers, including Pulitzer winners John Adams and Ornette Coleman.

Since 2002, the organization has organized the annual Bang on a Can Summer Music Festival at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

Segments

- Art & Design

- Music

- Dance

Transcript

Coming up on Articulate, a life in dance would not seem an obvious career choice for those with physical limitations. But choreographer Heidi Latsky doesn’t see disability as a disadvantage.

Heidi Latsky: This is not a pity party, this is not sentimental, and I work with people because I find them exquisite inside and out.

We all aspire to live better lives than those who came before us. For visual artist, Gary Baseman, this is his defining idea.

Gary Baseman:I didn’t have a fear that I wasn’t good enough. I just had a fear that I wouldn’t accomplish my goals.

AJC: But the goal moves.

Gary Baseman: Well, you accomplish something, but then you just keep having something you want to attain. Something you want to create. Something you want to prove.

And, you fight against the man until one day you become him, or her. Three decades in, the avant garde classical group, Bang on a Can are happy to be passing on their mantle of rebellion.

David Lang: We had a certain polemic when we started and the polemic was basically, old people should not tell us to stop. And now that we are the old people, we like the idea of not telling other people to stop.

That’s all ahead on Articulate.

Choreographer Heidi Latsky has spent her life cultivating self-awareness and working to reconcile the mind-body split. She performed as a principal dancer for the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company between 1987 and 1993. In 2001, she started her own company. Five years later, Heidi Latsky Dance hired a number of disabled dancers, putting the company at the forefront of a movement now called “physically-integrated dance.” But Latsky says her work is about ability, not disability.

Heidi Latsky: This is not a pity party. This is not sentimental. I work with people because I find them exquisite, inside and out.

For someone so accomplished in dance, Heidi Latsky came to the form later than most. She was a timid teenager, who had gone to college young and was already most of the way through a psychology degree when a handsome disco dancer brought her toe-to-toe with her calling.

Latsky: We had so much fun, and we started winning competitions, and I loved when he would twirl me, and then dip me, and then he would start lifting me, and we started practicing. We started competing more, and I just, I fell in love with movement. And I had danced a little bit as a kid, but I was, again, very shy so it wasn’t the kind of thing—it wasn’t an outlet for me. And so when I graduated and I was only 19, I thought, “Okay, I’m going to take a year off and I want to horseback ride, and I want to ski, and I want to keep dancing, and I want to try it.” It was so challenging, and it was my body, and I felt like I had been such an academic in my head that I really needed to move out of my head and into my body.

In 1983, Latsky moved to New York study dance, but struggled with teachers who told her she wasn’t good enough and a body that seemed to sabotage her progress at every turn.

Latsky: My body was always my enemy. In so many ways, I saw it as I had this horrible relationship with it because I was injured all the time. Also, when I started dancing, I did not have a dancer body. I was disproportionate. I had really huge thighs, and I was really small on top. And I’m small, so I was sculpting my body. I was trying to change it, but in the process, I was getting injured, because I was dancing when I was much older and pushing my body to do things that it really didn’t know how to do. I was always retraining, having to understand better, “Why? What?”

Seeking answers paid off. Not only does Latsky now have a profound understanding of her own body; she’s learned how to help others connect with theirs. It was while teaching a Movement for Actors class at the School for Film and Television in the late ’90s that Latsky developed her eponymous teaching practice, rooted in alignment and breathing-based exercises. And it was through this work that she connected with the woman who would become her muse—the late performance artist, Lisa Bufano.

Latsky: She had no lower legs and no fingers. But she was one of the most beautiful movers, beautiful performer. And I remember watching her and thinking, “Oh my god.” And it gelled for me. I love a performer who’s really vulnerable but really fierce. And she was that. Without any training, she had this kind of, “I’m going to do this,” but also so open. And that’s really hard to achieve, and especially if you’ve been a trained dancer, it’s kind of knocked out of you, ‘cause it’s not always taught. You’re so… You have to get your leg a certain height, you have to work so hard on the athleticism of it that sometimes people forget, “Well, who am I as the artist?” Which means, “Who am I? Can I dare to be vulnerable?” That’s hard. She had it.

And so, too, Latsky says, has every one of the dancers she’s worked with since.

Latsky: Anybody who has a disability, who’s never danced before and has the balls to actually join a professional dance company and perform, is going to have that. I think they’re going to have that already. And they have. Anybody who’s wanted to work with me has had that kind of quality. My job is to pull out their unique virtuosity. What is it they do physically that we can’t do? That I can’t do?

But bringing disabled dancers into her company presented a steep learning curve that Latsky continues to work through, one conversation at a time.

Latsky: I knew nothing about disability, and so I had to learn from them, “Well, what is appropriate? What’s the right terminology?” You don’t say “handicapped,” you don’t say “differently-abled,” all that. It’s a constant back and forth, because it is a complicated relationship. I am not disabled, right? And I’m leading a physically-integrated company. And so, my relationship with everyone in that company is important. For instance, my non-disabled dancers sometimes become invisible. It’s kind of interesting, right? So, when we’re performing, the critics don’t see them, because they’re so fixated on something that’s different. When I was in Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane, when I first joined the company, Lawrence Goldhuber was in that company. He was an unusually, really large man. You’d never see a big guy like that in a dance company. So he got so much attention. And I remember feeling like I was dancing so hard, so committed, and feeling like I wasn’t being acknowledged. I wasn’t being recognized. And he was, and I understand that syndrome, and I have that in my company now. Even post-performance talkbacks, everyone wants to talk to the disabled dancers. So some of my disabled dancers brought that up, and we started being more active about, “Okay, what happens when the audience is asking too many questions about disability, and we really want to talk about the art?” So we started devising ways to answer those questions, but then to move on so that everybody could participate.

AJC: So, when audiences really get it, how do you hope that they’ll react?

Latsky: I think the best reactions are when people see how beautiful it is. And it doesn’t become about disability. It just becomes about bodies in space and the beauty of what we’re creating on stage.

But what they’re creating on stage is also helping to redefine ideas of beauty in dance and beyond.

Growing up in Hollywood, Gary Baseman learned early to embrace ambition. He developed a remarkably clear artistic voice at a young age and was determined to put it to work however he could.

Gary Baseman: I didn’t have a fear that I wasn’t good enough, I just had a fear that I wouldn’t accomplish my goals.

AJC: But the goal moves.

Baseman: Well, you accomplish something, hopefully, or you fail at it miserably, which I’ve done many, many, many times. And I’ve accomplished a few things, too. But then you just keep having something you want to attain. Something you want to create. Something you want to prove.

Baseman calls what he does “pervasive art,” meaning that he wants you to risk bumping into it anywhere. Indeed, it seems that Baseman’s world is constantly being filtered through an artistic lens. Most of the time, he can be found with a journal in hand, a direct pipeline to his inner world.

Baseman: I don’t even want people, after I’m dead, to tear out the pages, because it’s on the next page. I want the book in its own right to be a work of art.

There are nearly 150 of these journals filled with a cast of recurring characters, all of which Baseman says are versions of himself.

Baseman: We live with so much desire and longing that we can’t even express. And so with Creamy, he falls in love easily, and just overheats and melts himself down. Just can’t control it, and I think that’s the way I’ve been since I was a little kid. I don’t think there’s a time. I was like a three or four-year-old. I was surrounded by girls all the time, and always falling in love, but never telling anybody and just melting myself down.

AJC: You were a really good kid, but you got angry.

Baseman: I was angry.

AJC: Really, even when you were a good kid?

Baseman: Even when I was a good kid, sure. But I was like a good kid, I would get angry. I would mess up the bed sheets. But then by the time my mom came, I would try to fix the bed. No, I mean, you have your own way. I did it through my art. Draw things in my own world. And that’s the thing, instead of confronting people through conversation or something, you find a way through my art to express some kind of truth that you may be even afraid to express.

Baseman has lately dedicated himself to seeking out some very particular truths. Since his father, Ben Baseman, died in 2010, Gary has obsessed over his parents’ Holocaust survival story. It was common knowledge that his father had been a partisan—a freedom fighter—but in 2012, a visit to their hometown in present-day Ukraine uncovered some long-hidden dimensions of his story.

Baseman: So in my father’s town, there was this book, and it told the story of my father, Ben Baseman—or his name back then was Burrow—who returned to his town at Berezne and discovered three men that were responsible for killing his parents, and what he did.

AJC: What did he do? Did he kill them?

Baseman: Well, in the book, they said him and another partisan, yeah, killed them. And then the town started talking about it, ‘cause it wasn’t, you know, normal kind of conversation for Jews to take retribution or revenge. And then he ended up in prison, and I think sentenced to death. And he was able to get out and escape with help, because he was a freedom fighter, he was a partisan. He spent three and a half years in the woods of Poland with these Russian paratroopers. And then he saved my mom, and then went to her relocation camp in Linz-Bindermichl. And then had a son, and then came to Canada, I think under false names, and then became Canadian citizens, and then came to America and became an American citizen. Once he died, and living with this, my world just kind of turned gray, that now, maybe I’m responsible. I’m responsible for his story, ‘cause this extraordinary story will be lost if I don’t tell it, ‘cause I know my brothers and sisters won’t. It’s just not who they are. So, watching that burden, it just kind of developed inside you, and that need, that “I need to find a way to understand this man, and why he wasn’t a crazy person, and why he was a character, but why he had such an amazing will of survival, and so optimistic, and especially with his children,” I think, “Wait, with what he went through, why didn’t he—how could he live that? How did he want to live to raise a family and give their kids the opportunity to be or do anything?”

(clip from Mythical Creatures):

Narrator: In 1941, it was easy to kill people. Killing people could be easily done.

Baseman is currently making a documentary about his family legacy. In the meantime, a traveling exhibition, The Door is Always Open—which features real artifacts from his childhood home—is already telling a version of the family story around the world.

Baseman: I still get people coming up to me, almost every day, just saying, “You know what? That was the best museum show I’ve ever been to.”

AJC: I’m just curious, do you think about the audience, or are you just making what you do?

Baseman: No, I think about the audience later. For me to find some kind of truth, I’ve got to hone in on myself, and that’s hard enough. But then, as an artist, how I want people to interact with it has changed and has grown. I would create these environments, and then work with dancers, or composers, or actors, and then would watch how people interact, or grow, or challenge themselves, how they think, or their own feelings. To make it something even more personal for themselves. So, like, with every medium in every way becomes more interesting of what to do.

In Gary Baseman’s art, it is easy to see his own continuing evolution, appraisals of his own personal experiences, and the truths he has learned.

Avant-garde classical group Bang on a Can is a primal clang in a world of metronomic conformity. The group has been interrupting norms since 1997, when members Julia Wolfe, David Lang, and Michael Gordon saw a need for refuge for people who didn’t align with the ideology of classical music at the time.

Julia Wolfe: When we came into the music world, there were very narrow bands.

AJC: The uptown and the downtown.

Wolfe: Uptown, downtown, there was this kind of heavy dogma coming from, at least from academia and from a lot of the major venues in the country. So that was frustrating to us, because we were children of many musics.

Michael Gordon: I think back then, everything was so polarized, and you were either… It was like “red state, blue state” in composition. You were on this team or that team, and they were at odds with each other.

David Lang: Part of our desire, when we started, was to think of ways to get people to look past those boundaries, so that people from different categories would find things and like things.

In lieu of trying to fit into an available box, these young composers made their own by forming a collective, and naming it, aptly, Bang on a Can.

Wolfe: Part of the title for Bang on a Can was also, we were motivated by, again, getting rid of the formality, but what tells everyone, “This is for everyone” or “It’s open to everyone”? So Bang on a Can is just very basic, I guess, one-dimensional. It’s just hitting a can.

In order to be heard, they realized they would have to create space for people who, like them, could probably describe themselves as renegades.

Lang: We started the first Bang on a Can Marathon, and we called it the “First Annual Bang on a Can Festival,” and we laughed ourselves silly, because we just thought, “We’re doing all this work ourselves. This is huge effort. We’re putting this whole thing together. We’re never going to do this again.” And by the end of the concert, it was really clear to us that people had showed up, that it had meant something. We’re three o’clock in the morning, we’re cleaning up, we’re trying to get out, and we just can’t believe that we’ve done it, and we sort of realized that we were going to have to do it again.

30 years later, the Bang on a Can Marathon is still held annually. Since its inception, the group has expanded to include not only Wolfe, Lang, and Gordon, but also a loose musical collective called the Bang on a Can All-Stars, the Asphalt Orchestra, a radical marching band, and a summer festival for young composers, held in rural northwestern Massachusetts. Their only guiding force over the past three decades has been in making interesting music, which they’ve learned often requires a blatant disregard for rules and boundaries.

Gordon: We just started out with curiosity. Everybody said, “No one wanted to listen to this music,” and we sat around and said, “Well is that really true?” And I think that’s how we started. And, for me, I think we exceeded expectations the first year.

Today, Gordon and Wolfe, who are married, live in the same Manhattan neighborhood as Lang, where they spend their days in their studios and on the telephone with each other, sometimes from within the same apartment.

Lang: And a lot of times, what happens with all of us is we sort of know what we want to do in a piece, but what we really need is someone who gives us permission to do it as much or as long as we would like. So what usually happens to me is I play something for them, I say, “I wrote this, it’s a minute long, and I really just want to do it for half an hour, but I think everyone’s going to hate it.” And then Michael goes, “They’re going to hate it anyway. Do it as long as you want.” And then I go, “Great, I’m going to do it for half an hour!”

Now that they’re a part of the establishment they once wanted to dismantle, the members of Bang on a Can realize a certain responsibility to younger people who think like they once did.

AJC: I hate to say this, but you guys are now “The Man.” You are now the middle-aged people who say things about the way the world can be in music. They are probably some upstarts around Brooklyn, looking at you and going, “Ugh, Bang on a Can. I’ve got your…” You know? You now are part of “the establishment.”

Wolfe: That’s good. That’s good. They should do that. We want to be a part of that connection to the next generation. I think composers that keep themselves isolated in their own generation is a big loss. You really want to have that dialogue with the next generation coming up.

Lang: We had a certain polemic when we started, and the polemic was basically, “Old people should not tell us to stop.” And now that we are the old people, we like the idea of not telling other people to stop.

And by simply being themselves, Bang on a Can have turned a void into a symphony.

On the next Articulate, young people are the antidotes to hopelessness. At least that’s what young adult author, Jason Reynolds believes.

Some will spend a lifetime searching for our calling. Cellist Alisa Widerstein found hers at age five.

And it’s been faced with tragedy that we find out who we really are. Naomi and Lisa Diaz’s musicality rolls from the ashes of loved ones. Join us for the next Articulate.