World of Words

Description

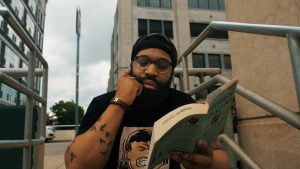

Writer Tochi Onyebuchi and visual artist Stephen Powers are both trying to change the world, one word at a time.

Featured Artists

Tochi Onyebuchi is an award-winning science fiction writer and former civil rights lawyer.

He was born in 1987 in Northampton, MA, to Nigerian parents, and raised in Connecticut. Onyebuchi earned a BA in political science at Yale University, an MFA in screenwriting at New York University, a master’s at L’institut d’études politiques in France, and a law degree from Columbia Law School.

He began writing novels while still in high school and published his first book, the young adult novel Beasts Made of Night, in 2017. Set in a fantasy world based on Nigeria, the work won the Nommo Award for African speculative fiction and spawned the sequel Crown of Thunder (2018).

Onyebuchi’s first adult novel, Riot Baby (2020), tells the story of a wrongly imprisoned boy born around the time of the 1992 Los Angeles riots and his supernaturally powerful sister. It was nominated for a prestigious Nebula Award for science fiction.

Stephen Powers is a celebrated artist and muralist, also known by the name ESPO (“Exterior Surface Painting Outreach”).

Born in 1968 in Philadelphia, Powers attended the Art Institute of Philadelphia and the University of the Arts before relocating to New York City in the mid-1990s. He became known for his guerrilla street art, painting abandoned shop fronts throughout the city and creating large faux-advertisements. After being arrested in 1999 for protesting Mayor Rudy Guilliani’s attempt to shut down an exhibition at Brooklyn Museum, Powers gave up graffiti to focus on studio art, sign painting, and commercial illustration. His art has been exhibited at museums and galleries around the world, including Dublin’s City Arts Centre, Brooklyn Museum, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

As a muralist, he is best known for his Love Letter series in Philadelphia (2009), Syracuse (2010), Brooklyn (2011), and Baltimore (2014). He wrote the 1999 book The Art of Getting Over about graffiti artists and their work, the short story collection First & Fifteenth (2005), and the art book Studio Gangster (2007).

Segments

- Art & Design

- Literature

Transcript

Welcome to Articulate, the show that explores the big ideas behind great creative endeavors. And on this episode, “Worlds of Words.” Writer Tochi Onyebuchi imagines worlds that never were, but always grounds them in this one.

Tochi Onyebuchi: I don’t know that we’re capable as human storytellers of getting to a place where we inhabit a completely alien consciousness that is completely devoid of human experience or emotion, or any sort of linkage to our lived experience.

And Stephen Powers wants the murals he creates to be democratic and reflections of the communities they occupy.

Stephen Powers: If you do something that people appreciate and they don’t complain about it, that’s a really sweet spot to be in like that’s…there’s power and beauty.

That’s all ahead on Articulate.

As the child of Nigerian immigrants, Tochi Onyebuchi has always wrestled with his identity as a Black American.

Tochi Onyebuchi: Oftentimes, I’ve felt like an interloper in the African-American experience even though all these external cues are lumping me into that same bucket so, you know, my parents didn’t live through the Detroit race riots. There’s no real, you know, historical, you know, lived tangible connection between me and the civil rights struggle, but I benefit from these things by virtue of my color. And so, when Black Panther comes out and it’s cool to be from Africa, you know, I get to walk around with this privilege.

That ambivalence has manifested in his writing. From an early age, Onyebuchi wanted to be a storyteller and would grab at any chance he got to write, but it wasn’t until he was in his mid twenties that he included characters who looked like him in his stories.

Onyebuchi: It was the very first time that I wrote Black main characters. The very first time in my entire life and writing career. I just wasn’t imbibing, particularly, speculative fiction wherein people who looked like me were the main characters. It just like wasn’t, it wasn’t readily available to me.

Born in Massachusetts in 1987, Onyebuchi was the oldest of four children but his adolescence was cut short the day before his 11th birthday, when his father died of cancer. Onyebuchi’s mother began working multiple jobs to provide for her family. He felt obliged to help ease her burden, but that sense of responsibility held him back from his own grief. He was diagnosed with depression in high school and later with bipolar disorder. He started drinking heavily and became what he’s described as a raging alcoholic. He was in his mid twenties when he quit, but all the while he was somehow also nurturing his writing. Onyebuchi was especially drawn to the escapism of speculative fiction of science fiction and fantasy.

Onyebuchi: You can have work that’s so busy, there’s so much going on. There’s not just the story that you’re reading on the page. There are all these other levels and allusions and whatnot that you can unpack. And that’s something that I also really, really, really appreciate about science fiction and fantasy. You can live with a book. Any free time that I had, I was writing. If I had a free period in the middle of the day, I was writing. If I finished my homework early into study hours, I was writing until lights out. On the weekends, it was an absolute boon, you know. I didn’t go out to parties or things of that sort, you know, a terrible amount ’cause I was always busy writing. And the thing about it was, I didn’t… I never felt as though I was missing out because I loved writing so much.

By high school, Onyebuchi estimates he was already writing a novel a year, 16 of them before he ever got published. But storytelling, he surmised, could never be a career, rather something he squeezed in around a real job. And so as he began law school at Columbia, he realized that he wasn’t just stealing time to explore his ideas. His studies were helping to expand them.

Onyebuchi: It was in law school that I really got immersed into the issues of incarceration, both overseas and in the United States, and that changed my life. The African-American experience was very much an academic item in my life but then, like I started knowing people who went to jail. I started personally knowing people who went to prison. I started personally knowing people who got sort of chewed up and spit out by these systems and you know, it…that made it real in a way that it wasn’t necessarily real for my parents’ generation.

Onyebuchi’s legal training became a tool kit for him to dissect increasingly complex realities through increasingly complex fiction. In the years that followed, as public awareness of police killings of African-Americans grew, so too did Onyebuchi’s need to make sense of it all.

Onyebuchi: I knew that there was something sort of maybe poisonous, sort of festering in me. It was this combination of rage and hopelessness and so many other things, but I knew I needed to get it out of me. I knew I needed to expel it somehow and the way that I organize the universe is through writing that’s how I’m able to sort of articulate so much and when you can sort of articulate the shape of the monster before you, it all of a sudden becomes a lot less intimidating.

Riot Baby was the outcome of that articulation. The book follows two black siblings: Kevin who becomes imprisoned, and his sister Ella who has supernatural powers.

Onyebuchi: I didn’t necessarily see a protagonist who was a young black woman who basically, you know, had the powers of a God. I’d never seen that before. And, you know, growing up in South Central surrounded by gangbanger culture, living through the Rodney King uprising, you know, being in Harlem during the 2000s and developing this, developing this incredible power. But being incredibly angry at the same time and trying to figure out where that anger is coming from—that was very compelling to me. There’s almost a sense of Greek tragedy to it where, you know, you can do whatever you want, essentially, with these powers except for this one thing. And it’s the one thing that you want more than anything to be able to do, which is protect your younger brother.

Riot Baby was a finalist for the Hugo and Nebula Awards, two of the highest honors in speculative fiction. But fantasy writing wasn’t just a way for Onyebuchi to connect to massive political struggles. It also helped him to grapple with something more intimate, his own family’s tangled history. Onyebuchi’s mother grew up in Nigeria during the Biafran War. After hearing about her experiences, he wrote War Girls, a novel set in 2172 which follows a similar civil war.

Onyebuchi: I had heard in an off-hand comment as we were driving back from some family friend’s place during some holiday season, Mom mentioning having to live in the forest for a period of time with her family, just an offhand comment and then we were talking about something else. And I was like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa! Hold up a second, can we like rewind?” And she went into this whole, you know, story about being an internally displaced person in Nigeria during the civil war, which started right after she’d finished kindergarten. There’s this question that I ask myself or at least asked myself during the composition of War Girls was, you know, “By forcing my mom to excavate these memories, am I re-injuring her?”

AJC: Did you ask that question as you are asking for the stories?

Onyebuchi: Yes, I asked my—

AJC: And she tutted and said “I’m made of sterner stuff, son”?

Onyebuchi: Well, she is…I mean, she’s incredibly stoic, right? And it, you know, part of that is the, you know, completely living into the immigrant stereotype of, you know, you just sort of keep it moving. You don’t let anything stop you. You do all these impossible things so that your, you know, your children and their children can have the much better life and it’s the American dream, right? So she was very stoic about all of it and very, you know, very generous with her time and with her memories and things of that sort. But I could not help this sort of creeping guilt that I was putting her through something or that, you know, to a certain extent that I might’ve been causing her any sort of pain.

Still, Onyebuchi worked through any guilt he felt. War Girls wasn’t only a chance for him to write about his mother, but also to write with her.

Onyebuchi: What was actually really meaningful was at a certain point towards the end of the writing of the book, I had to submit a pronunciation guide to Razorbill. And so, I went through with mom over all the words that they had questions about and she recorded pronunciations for them. And, you know, even looking back on that memory now I have to like, you know, I have to control my emotions a bit because it seemed like in many ways, the culminating moment of what I’d been trying to accomplish with this book, personally, which was to get closer to mom. It just felt like there was this abiding love, ’cause it also felt like…it also felt like validation of my career choice. So there’s that aspect of it too where, you know, she’s helping me be a writer, she’s helping me write a thing.

Tochi Onyebuchi has navigated his life by latching onto the core tenet of science fiction and fantasy: oftentimes, to understand the world better, we have to create and explore new ones.

Onyebuchi: As human storytellers, I don’t know that I’ve come across a story yet where there isn’t that connection, I don’t know that we’re capable as human storytellers of getting to a place where we inhabit a completely alien consciousness that is completely devoid of human experience or emotion or any sort of linkage to our lived experience.

Tochi Onyebuchi fills his stories with magic, telekinesis, space colonies, and cyborgs. But under-girding it all is a voracious curiosity to connect how and why people behave as they do in a world that can seem unrelenting, unpredictable, and unfair. And while he hasn’t found answers to all of his questions, he’s dedicated to creating vast new worlds where he just might.

Stephen Powers went to jail in 1999 following a police investigation of him for vandalism. But this brush with the law changed nothing and everything for a man who sees himself as part of a tradition that stretches back millennia.

Stephen Powers: I think of myself as a modern day cave painter, like that makes the most sense to me. It always has, like, graffiti was just trying to figure out like what I could do to transcribe the day-to-day operations and put them in front of people and hopefully communicate what it means to be alive.

And this modern day cave painter, today, sees himself as something more prosaic yet somehow also more poetic.

Powers: I think a middle-age, middle-class sign writer covers it. But, what I love about sign writing is sign writing is so…it’s so blue collar, but it’s also so completely creative. And, you know, generally every sign writer I’ve ever met is an artist.

Born in 1968, Stephen Powers discovered the possibilities of the walls of his Philadelphia home by age three. They became his canvas and his crayons his tools. He indulged his caveman tendencies wall by wall. As a teenager in the early 80s, he turned to street art. He joined his contemporaries, tagging their signature styles on walls of abandoned buildings, on the rooftops, seen from the city’s elevated train. And it was his salvation.

Powers: What I write and what I draw is me drawing from life, from the everyday trials and tribulations, trying to make sense of it. It’s almost as if I’m creating like a life raft every time.

The fifth of six children, Powers is candid about his flawed family and the issues that daily drove him out of the house. His parents, early pioneers in computer programming, met at the University of Pennsylvania. They agreed upon and soon achieved Aristotle’s prescription for the ideal family: two boys and two girls. But when Stephen and his sister came along, the fifth and sixth, his father, a gifted inventor, felt betrayed. And so when Powers was 15, his dad abandoned the family.

Powers: And that was perfect for me ’cause I now had a clear road ahead of me to do the things that I wanted to do, which was predominantly writing graffiti and figuring out like what that was and how I can make something of myself with that, if I could.

Left alone to raise the kids, his mother grew increasingly bitter with their threadbare existence. His baby sister got some love, but he felt like a leftover. At 16, he grew tired of self-pity and took to the street. He invented his own graffiti tag ESPO, incorporating his initials. It sounded vaguely official and soon started showing up around Philly. When someone would challenge him on the street, he would tend to working for ESPO—Exterior Surface Painting Outreach—and it worked, for a while.

Powers: I was raised on TV in the 70s, in the 80s and you know, my mind’s…my mind was probably already soft to begin with. But, you know, rapid fire editing and MTV and, you know, logos and soundbites and, you know, short attention spans, like I cater to all that ’cause that’s where I grew up.

That brush with the law for criminal mischief came after a 1999 police search of his Brooklyn studio that seized art materials, photographs, computer hard drives, and pages from a forthcoming book, The Art of Getting Over: Graffiti at the Millennium. Powers and his attorney believed the arrest had been politically motivated, that he had been targeted for protesting then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s attempt to censor a Brooklyn Museum exhibition. For Powers, his only crime then and thereafter was pursuing his calling. Like generations before he sees graffiti as free expression. Splashing paint on walls with words and pictures has meaning.

Powers had moved to New York in 1994. That same year he visited a friend and fellow artist at his studio in San Francisco. This spurred Powers to open his own gallery and studio. ESPO’s Art World at the corner of 4th and Bergen in Brooklyn is Powers’ creative headquarters. One prominent sign on the outside of the building declares, “Perfection is Standard, Mistakes Cost Extra.” It was from here in 2003 that Powers unleashed his sign writing prowess on Coney Island. With fellow artists he developed traveling sign shop ICY Signs, creating colorful hand-painted signage and advertisements for local businesses. This established a new Coney Island style of painting which in 2015 the Brooklyn Museum of Art paid homage to with the exhibition “Coney Island Is Still Dreamland (To A Seagull).” Powers calls the museum the nicest cave he’s ever painted.

But a more pivotal collaboration in Powers’ life had happened earlier when he met his future wife Maryanne. Not only did he find a supportive spouse, but a more stable family than the one he had grown up in. Her parents and siblings welcomed him with open arms. He called his mother-in-law Dorothy Long, a master potter and entrepreneur, his art mom. And in his new father-in-law Al Long, he had found a man fully committed to his family. After Al died in 2019, Powers, now with a son of his own, formulated what he called the reciprocal deal between parents and children in a story titled, “Raise Me and I’ll Raise You,” part of the collection First and Fifteenth: Pop Art Short Stories, published in 2005. Stephen Powers’ experiences with his own father and with Al informed his own approach to raising his son. He resolved to be as invested as a father as his own dad had never been.

Powers: I feel like before—there was a time when everything I made was cynical and it was still funny but it was cynical, it was dark, like the darker the better. It couldn’t get dark enough from it. But I had a kid and, you know, in that second when you’re suddenly, you know, you’re a father and you’re suddenly like a part of a family. Your whole worldview just like changes. Literally, a life came into my life and everything from that point on became life affirming. I am a father to him and I thank my father for, you know, my father did, he did a few great things for me.

Though Stephen Powers’ father was an avid gun collector, he preached against their actual use, teaching his son how to unload but never how to load or to shoot. A confusing attitude towards firearms to be sure, but Powers was never confused and, in 2017, he illustrated a series of nine essays about gun violence for Vogue Magazine, bringing to life the words of the survivors of gun violence. Stephen Powers’ work has always leaned towards the pithy, the straight-forward. His larger than life murals marry words and pictures to profess love and pledge devotion. And the work he makes comes out of both the oldest and the newest forms of human communication.

Powers: I love those stories that are so short and they get passed around like dollars. You know, like the joke you told and, you know, they’re really small, easy ways of just transmitting humanity, you know, and very easy to remember, easy to pass along. The first bit of artwork that was drawn on a wall that we know of is 65,000 years old and it’s a ladder. In depicting a ladder, the person that drew that ladder depicted technology, they made a story, they depicted a way forward, you know, and it’s something that speaks to me all this time later, like I drew a ladder yesterday, like I draw ladders all the time. A ladder laid out on the ground turns into train tracks, you know. So, these are the things that convey us going to our next station, rising up a little bit. And it’s useful to know that no matter how terrible things are, no matter how stuck we seem to be, a ladder is a way forward, train tracks are a way out.

Although Powers works around the world, he’s often back in his hometown. He remembers being a kid riding the El, the elevated train in West Philadelphia, and the way his eyes were constantly drawn to the graffitied rooftops.

Powers: Just like me, it was like hundreds of teenagers that were finding themselves and being themselves. And it was like the most beautiful, powerful thing to me, and I contributed to it. You know, I painted a few rooftops myself and I felt like I just added to this tapestry that was gonna last for hundreds of years, you know. There’s no reason for it not to last.

But it didn’t last. In 2008, he noticed that Philadelphia’s Anti-Graffiti Network had painted over all the rooftops. This official act of destruction hatched one of his most well-known works, a mural series called “Love Letters”. A Love Letter For You is a series of 50 murals that runs along the 20 blocks stretch of that same Market Street El. They express love from a boy to a girl, and from a man to his city. This was his chance to make something that people might care about and hopefully enjoy for years. But almost before the paint was dry on his first work, an overzealous operative from the Anti-Graffiti Network had whitewashed it.

Powers: All the forces of good aligned behind me, this guy just painted right over it. And, you know, we caught up to him immediately and I asked him like, “What were you thinking?” And he goes, “I knew that was you.” Like, he remembered me from 15 years before or whatever. I was like, “Well, I’m doing it again.” And it was easier to do the second time.

13 other cities around the world have since invited Powers to create love letters. With input from local residents, he and his crew create poignant affirmations stitched together to reflect the hopes and dreams of each community. In Charleroi, a small Belgian industrial town south of Brussels, the key concept came from one person on the local team, who when asked what he might say to his grandchildren said, “Bisous, m’ chou.”

Powers: You know, “bisous” is kisses, “m’ chou” was like very specific to this region. They say it in different ways but in the particular way that they said it and we spelled it, it was like theirs.

Now in his early 50s, Stephen Powers still believes that graffiti has a place in urban culture. And he believes that if people find value in the work, it will survive. His philosophy: let the people be the judge.

Powers: And it was the first thing that I learned was, if you do something that people appreciate and they don’t complain about it, that’s, that’s a really sweet spot to be in like that’s, there’s power and beauty. I painted a Black Lives Matter mural in Union Square and it got defaced, you know, and the owner of the property who gave me the wall to paint, who’s been a great steward of the wall, she’s a really awesome theater impresario, she was really depressed by it, you know, she was like, “Ah, I just feel so bad that somebody would do that.” And I said, “It’s just paint. It’s four cans of paint. It’s a lovely afternoon.” She’s like, “Wow. I feel a lot better. I feel a lot better about that.” I was like, “Yeah, the next time, like, you know, somebody writes on the front of your theater, keep it in perspective. You know, it’s just paint.”